Remember the days of LimeWire and The Pirate Bay? They are far behind us now, thanks to the likes of streaming services such as Netflix and YouTube, which have made entertainment affordable and accessible at our fingertips—as long as we have a stable Internet connection.

Singaporeans must be having a blast on these platforms, then, considering how we have the highest online presence in the world, with an Internet speed that’s only rivaled by Norway.

In fact, according to Statista, since Netflix rolled out in Singapore last January, local subscribers have more than doubled, growing from 47.5K to 98.9K in just a year. YouTube receives the same ardour, overtaking Facebook to rank as the top social media site in Singapore.

Are Streaming Services Such As Netflix & YouTube Killing The Television?

The question, which surfaced on the Internet as early as 2009, must have been asked a thousand times; but, as foreign streaming services pick up steam in Singapore, the concept is worth revisiting in a local context.

According to a recent survey conducted by marketing agency Kantar TNS, more than 3 in 4 connected consumers in Singapore are tuning in to online videos on a daily basis—that’s slightly higher than the number of viewers watching traditional broadcast television (at 71%).

Does this herald the impending doom of the local television industry in the face of such progressive game changers?

Yes, Netflix & YouTube Are Killing Local TV.

To a certain extent, the above statement is true. Local television comprises both free-to-air stations and paid television services such as Singtel TV and Starhub TV, but both services saw a drop in the number of their subscribers last year.

According to The Straits Times, StarHub saw a 35,000 drop in the number of its subscribers last year, while Singtel lost 11,000 subscribers in the first two quarters of its 2016-2017 financial year.

Starhub had attributed the decline to the completion of contracts from a larger-than-usual proportion of its pay-TV subscriber base, but it also struggles to retain these subscriber’s loyalty in light of audacious competition from alternative viewing services (such as Netflix).

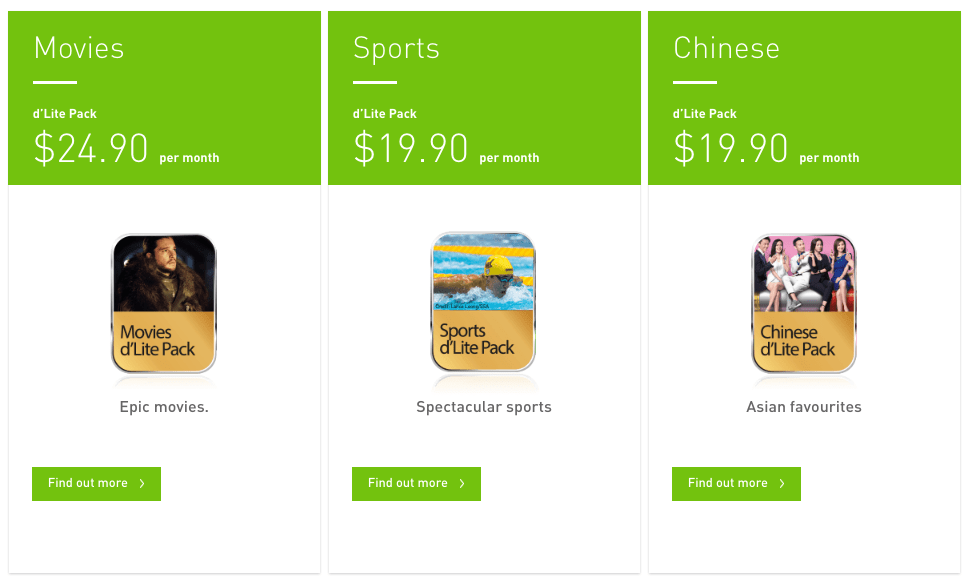

Pay television seems to be in the biggest peril here—it might struggle to stay afloat if services like Singtel TV and Starhub TV can’t offer more competitive subscription costs. For example, Singtel’s cheapest starter packs cost $18.90 per month and Starhub’s cheapest subscription (the d’Lite pack) starts from $19.90 per month.

In comparison, a Netflix subscription only costs $10.98 monthly.

Of course, one can argue that Netflix doesn’t provide the average Singaporean consumer with a satisfactory variety of entertainment like pay television does, but it is well on its way with their own successful brand of original series (‘Stranger Things’ comes to mind).

To this point, it is commendable that Singtel has an exclusive tie-up with Netflix that allows local Singtel subscribers to access the service via their set-top box if they wish to migrate their Netflix experience from a 13-inch screen to a 50-inch one.

But then again, if I wanted to watch Netflix on my smart TV, I would just connect it to my laptop with a HDMI cable. The delivery of content to my senses is the same, which is also why my family is among those who have cancelled their Singtel TV subscription.

However, On The Flip Side…

Free-to-air television continues to be the top platform for local audiences to consume news and entertainment. According to the annual Nielsen Media index Report that was released towards the end of last year, TV viewership even grew by six percent from the same period last year.

At the heart of this is Mediacorp, Singapore’s leading media company. Mediacorp’s success is attested by local and unique content such as blockbusters like ‘The Little Nyonya’. In addition, by buying the rights to and adapting popular Western games shows such as ‘Who Wants To Be A Millionaire’ and ‘The Weakest Link’, it created another bank of distinctive, localised content that it could cash in on.

When these series were first introduced in the early 2000s, they were so popular that Channel 5 increased the proportion of hours of game shows it aired from 8 to 20 percent in just four months.

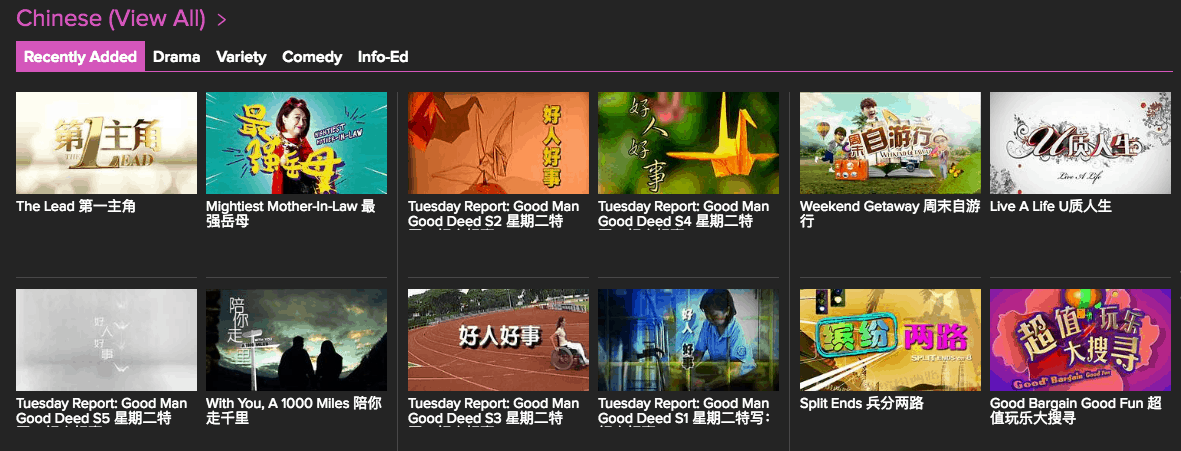

Producing some 1,600 hours of entertainment content in four languages a year, no one will rival Mediacorp’s bank of homegrown content. This brought about a mutually-beneficial opportunity between the local media company and the foreign streaming service: at the start of the year, more than 20 Chinese television series were made available to global audiences on the Netflix network. This gave Netflix more content to decorate its platform, while Mediacorp enjoyed greater global exposure.

That is to say, streaming services aren’t completely culling local television, although it has shown signs of jeopardising the revenue of pay television. Local television isn’t dead, it’s simply different as it adapts to ever-changing consumer habits.